-

-

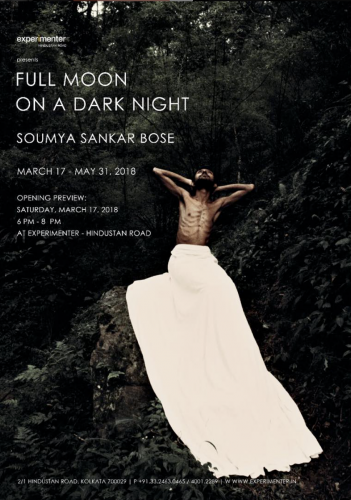

The Supreme Court ruling of September 2018, rescinding the law that criminalised homosexuality, is regarded by many to be a milestone judgment in Indian legal history. For the sake of appearances, the nation took a giant liberal leap.

The terms ‘façade’ and ‘appearances’ are intricately woven into the fabric of this ruling. The effectuality of a law is determined by the people who are governed by that law, and decriminalisation of homosexuality does not necessarily destigmatize the same from the psyche of the masses. Full Moon on a Dark Night is an exploration of appearances that were born out of a reaction against heteronormativity. In India an individual needs to inculcate a heteronormative demeanor to be accepted within wider social circles.

This work was started in 2015 – way before the Supreme Court ruling. One of the most prominent social aspects that has been noticed in the process of completion of this work is that the new law scrapping Section 377 has done very little in the way of expanding the social definitions of sexual normalcy. The contours of popular psyche has not changed much since 2015, or even before that; and this can be corroborated through the fact that well-constructed appearances still form a part of the daily lives of many people from the LGBTQ+ community.

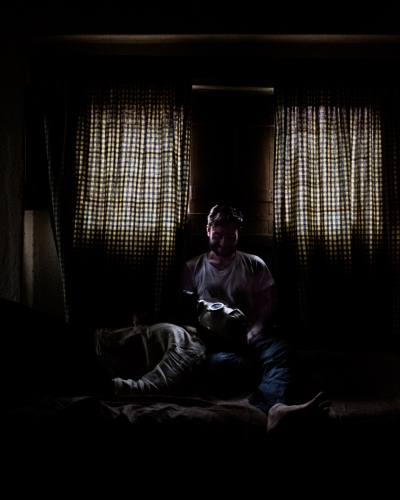

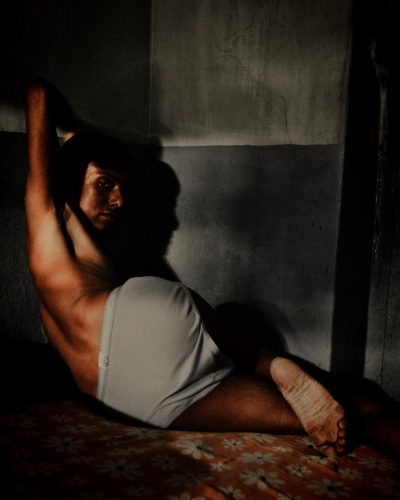

Full Moon on a Dark Night delves deep into this very appearance that people residing outside the boundaries of heteronormativity have to affect on a daily basis. More than the context of sexuality, Soumya has tried to focus on appearance as performance. It can be easily realised that one of the primary domains of conflict in gender and sex is the physical appearance of an individual and how the perception of that appearance is directly linked to sexual identity.

This work deals with narratives that are crucial in our times. Soumya was most certain about this when he got to speak to one of his friends and unearthed a deep-seated trauma in her life. She told him of a dream she had been having frequently. She dreams that she sits on a chair beside a window in the room in which her sister died. In the dream she returns home from an unknown war while a dead body lies in the bed. The identity of the dead character is never clear to her. Moreover, the dead person is adorned in the attire of a warrior. The vision has deep connotations that suggest the daily war a person has to wage with herself and the world around her as a price of sexual preferences. Did the corpse belong to her sister? Was she fighting for acceptance? Or, was it the culmination of her mother’s firm belief that she could not fall in love with another woman?

Another aspect should be brought to light in this context. The work in itself, though focusing upon the personal experiences of many of the creator’s acquaintances, is highly impersonal in nature. This fact will gain precedence since personal reactions are always remarkably different from impersonal ones. While we are not much concerned about the qualitative differences between the two at this stage, the mention of this facet is important. Soumya has been able to learn about the experiences of his friends, but he was not a part of the process of their growing up. A detachment of this nature evokes a distinct reaction in the person to a particular situation, and this reaction evolves with time.

Despite having Section 377 revoked, the people of the country are far from redefining their notions of normalcy. And this particular trait, time and again, forces countless people into a performance of affecting identities.

As many of Soumya’s works employ the tool of re-enactment, many of the ‘actors’ in the pictures had to evoke a certain style of performance in order to uphold the desired appearance in front of the lens. One may wonder about the parallels that such an act creates between real life and reel life; between a person defined by sexual orientation and a community identified as storytellers.